Written by Professor Jo Porter, marking UCL’s 200th anniversary this year

Wilson Fox was a prominent 19th century physician and pathologist who made significant contributions to the understanding of many diseases during his time at University College London (UCL) and University College Hospital (UCH, now UCLH), but I know him best for his work on pulmonary fibrosis, also known as interstitial lung disease (ILD) – which Fox termed ‘chronic interstitial pneumonia’.

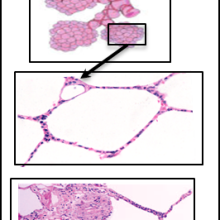

It was Fox who first described the pathology of ILD, the role of the alveolar epithelium and vasculature and the laying down of extracellular matrix that led to what he described as ‘cirrhosis of the lung’. His early descriptions set the scene for research into this devastating lung condition, which to this day continues at UCL Respiratory alongside an NHS National Referral Centre for ILD at UCLH and the UCLH Charity, Breathing Matters, established to raise awareness of, and funds for research into, lung fibrosis.

Early life and education

Fox was born to a Quaker family in Somerset on 2nd November 1831, just 5 years after the foundation of the new UCL – and it would be at UCL that Dr Fox would establish his reputation as a brilliant academic clinician, carrying out both ground-breaking research and writing the definitive textbook of lung pathology, published in 1891 shortly after his premature death.

Fox was born to a Quaker family in Somerset on 2nd November 1831, just 5 years after the foundation of the new UCL – and it would be at UCL that Dr Fox would establish his reputation as a brilliant academic clinician, carrying out both ground-breaking research and writing the definitive textbook of lung pathology, published in 1891 shortly after his premature death.

At just 15 years old, the young Wilson won a place at UCL from which he graduated in 1850 with a Bachelor of Arts, and in 1854 with an M.B., clinching the prestigious Fellowes gold medal for the highest graded student. After his qualification in medicine, he became a House Physician at Edinburgh Royal Infirmary.

After completing his medical doctorate (M.D.) in 1855, at the age of 24, Dr Fox went on an extensive tour of medical schools across Edinburgh, Paris, Vienna and Berlin. It was in Berlin, under the tutelage of the renowned Rudolf Virchow the German physician often called the “Father of Modern Pathology,”, that Fox focussed on anatomy, publishing his observations as “Contributions to the Pathology of the Glandular Structures of the Stomach” in 1858. Virchow’s cell theory and his emphasis on the cellular basis of disease had a profound impact on medical thinking in the 19th century, including Fox’s own approach to studying the lungs, and in particular pulmonary fibrosis.

Early career

In 1859, Dr Fox was appointed physician to the Royal Staffordshire Infirmary and established a successful medical practice in Newcastle-under-Lyme. Two years later, he returned to London, becoming a professor of pathological anatomy at UCL and assistant physician at UCH with the support of Virchow. The young professor made his mark and was soon promoted to physician (consultant) in 1867, exchanging his anatomy chair for the Holme professorship of clinical medicine, a position that no longer exists. In 1870, he was appointed physician extraordinary to the Queen, and elected a Fellow of the Royal Society. He afterwards became physician in ordinary (a promotion to become the main physician attending the royal household), and frequently attended Queen Victoria while in Scotland and indeed was consulted during Prince Albert’s fatal illness in 1861. With the royal seal of approval, Fox had no problems acquiring a large practice and was an active member of the leading medical societies and of the College of Physicians. He was ahead of his time in considering the whole patient in a holistic manner, which was very unusual for the 19th century, and he was also the first physician to advocate ice baths, in this case to save life in cases of rheumatic fever where the temperature was excessively high.

Pioneering work and publications

Professor Fox’s impact extended beyond the court and the consulting room. In 1873, he published “Diseases of the Stomach,” a work based on articles for Reynolds’ System of Medicine, but it was his pioneering work on the lungs, particularly phthisis (tuberculosis), that solidified his legacy. Challenging the prevailing belief, Professor Fox considered tuberculosis a distinct process, a perspective validated by Robert Koch’s later research.

Professor Fox’s impact extended beyond the court and the consulting room. In 1873, he published “Diseases of the Stomach,” a work based on articles for Reynolds’ System of Medicine, but it was his pioneering work on the lungs, particularly phthisis (tuberculosis), that solidified his legacy. Challenging the prevailing belief, Professor Fox considered tuberculosis a distinct process, a perspective validated by Robert Koch’s later research.

His magnum opus, “A Treatise on Diseases of the Lungs and Pleura,” was published posthumously in 1891, alongside the “Atlas of the Pathological Anatomy of the Lungs” in 1888. In this seminal work, he provided meticulous descriptions of ILD / “fibroid phthisis” or “chronic interstitial pneumonia.” His detailed observations of the accumulated pigmented epithelium in the alveoli, thickening of alveolar walls and the formation of scar tissue were crucial in establishing pulmonary fibrosis as a distinct clinical entity, although Fox was not entirely clear that this was not due to tuberculosis. In addition, in his cohort 37 of 39 patients with pulmonary induration had bronchodilatation, which we now call traction bronchiectasis, due to fibrosis. Fox was aware that he was standing on the shoulders of previous giants and credited Sir Dominic Corrigan for first pointing out tractional bronchiectasis and Dr Carl Rokitansky for recognising the alveolar fibrosis as the key abnormality in ILD.

Teaching and mentorship

As a teacher, Fox’s enthusiasm and thoroughness left an indelible mark on his students, including the renowned Sir William Osler. William Osler, often referred to as the “Father of Modern Medicine,” was a Canadian physician who revolutionised medical education and practice. Osler was younger than Fox, and their paths crossed during Osler’s time in London. Osler was based in the physiology department at UCL, but, in spare hours, attended the ward clinics of William Jenner and Wilson Fox. Fox, already an established figure at UCH, likely served as a mentor and colleague to the younger Osler.

Later life and legacy

Tragically, Professor Wilson Fox’s career was cut short in May 1887. While en route to his home at Rydal, he sadly yet ironically succumbed to pneumonia, aged 55 years old.

His contributions to the understanding of lung diseases, particularly tuberculosis and lung fibrosis, remain a cornerstone in the history of respiratory medicine at UCL. Professor Fox’s enduring impact continues to shape research, reminding us of the brilliant minds that have graced the halls of University College London.

Breathing Matters builds upon the foundation laid by researchers like Fox, making use of modern scientific techniques and a patient-centred approach to understand pulmonary fibrosis.

One of the key areas where Breathing Matters has made significant progress is in the field of personalised medicine. By studying the genetic and molecular profiles of individual patients, researchers aim to develop tailored treatment strategies that can more effectively combat the disease. This approach echoes Fox’s recognition of the varied manifestations of pulmonary fibrosis and meticulous attention to an holistic approach to care in individual cases – which we now call personalised or precision medicine. While the tools and techniques have evolved dramatically since Fox’s time, the fundamental goal remains the same: to understand, treat and ultimately cure pulmonary fibrosis.

One of the key areas where Breathing Matters has made significant progress is in the field of personalised medicine. By studying the genetic and molecular profiles of individual patients, researchers aim to develop tailored treatment strategies that can more effectively combat the disease. This approach echoes Fox’s recognition of the varied manifestations of pulmonary fibrosis and meticulous attention to an holistic approach to care in individual cases – which we now call personalised or precision medicine. While the tools and techniques have evolved dramatically since Fox’s time, the fundamental goal remains the same: to understand, treat and ultimately cure pulmonary fibrosis.

Wilson Fox 2.11.1831 – 3.5.1887, BA Lond (1850) MB (1854) MD (1855) FRCP (1866) FRS

Fox’s principal writings on the lung:

Fox’s principal writings on the lung:

- On the Artificial Production of Tubercle in the Lower Animals, a lecture before the Royal College of Physicians, 1864.

- Articles on Pneumonia, &c., in Reynolds’s System, iii. 1871.

- Atlas of the Pathological Anatomy of the Lungs, 1888.

- A Treatise on Diseases of the Lungs and Pleura, 1891.

Credits to:

Wikipedia Interstitial Lung Disease by Om P Sharma

[Posted January 2026]

Recent Articles

- Dr Wilson Fox: a 19th century pioneer in pulmonary fibrosis

- New research offers hope for IPF

- Christmas 2025 Newsletter

- A Christmas and New Year message to our supporters

- A: What Is Pulmonary Fibrosis?

- B: PF versus IPF

- C: Who is at risk from pulmonary fibrosis?

- D: Can pulmonary fibrosis be prevented?

- E: What are the symptoms of pulmonary fibrosis?

- F: How do you diagnose pulmonary fibrosis?

- G: What are the treatments for PF?

- H: Can lifestyle changes help in PF?

- I: Managing PF after diagnosis

- J: What are the stages of pulmonary fibrosis?

- K: Is there a cure for pulmonary fibrosis?